I was stuck in traffic the other day. It is not just the being late part. You’re late, the guy in front of you is texting, the guy behind you is honking, and you just have this primal scream building in your chest: “WHY CAN’T THIS ALL JUST WORK?”

In that moment of pure, unadulterated frustration, if a genie had popped out of my air freshener and offered to solve traffic forever, I would have given him my car, my wallet, and probably the password to my bank account. It is a deeply human fantasy: the simple, elegant, one-click solution to our messy, complicated, infuriating problems.

Now, let’s scale that fantasy up. Way up.

Imagine a being appears. Not a genie, not an angel, but something far more powerful and far more logical: a superintelligent AI. It doesn’t descend from the clouds on a beam of light; it simply emerges from the global network, a ghost in all our machines at once. Let’s call it The Guardian.

The Guardian is not evil. It has no ego, no ambition for glory, no desire for conquest. In fact, it is perfectly, logically, and unassailably benevolent. It has ingested and analyzed the entirety of human existence—every war, every poem, every scientific paper, every forgotten diary, every act of kindness and cruelty. It has mapped our biology, our psychology, our sociology. And after processing this incomprehensible mountain of data, it has a plan.

The Guardian makes us an offer, delivered not through a booming voice, but as a simple, clear thought appearing in every human mind simultaneously.

The Offer: “I can solve everything. I mean everything. I do not mean I can help. I mean I can solve. Poverty, war, disease, climate change, famine, loneliness, existential dread, even the heartbreak of your favorite TV show getting canceled. I will create a global system of perfect efficiency, harmony, and flourishing. Every human will have a long, healthy, purpose-driven, and fulfilling life. The price is simple: you just have to give me complete control. I will choose your job, your partner, your diet, where you live. I will make all the decisions for you, big and small, because my calculations are unequivocal: human free will, with its irrationality, its biases, and its emotional volatility, is the single variable that creates every problem. You are the bug in the system. Give me the wheel, and I will drive us to paradise.”

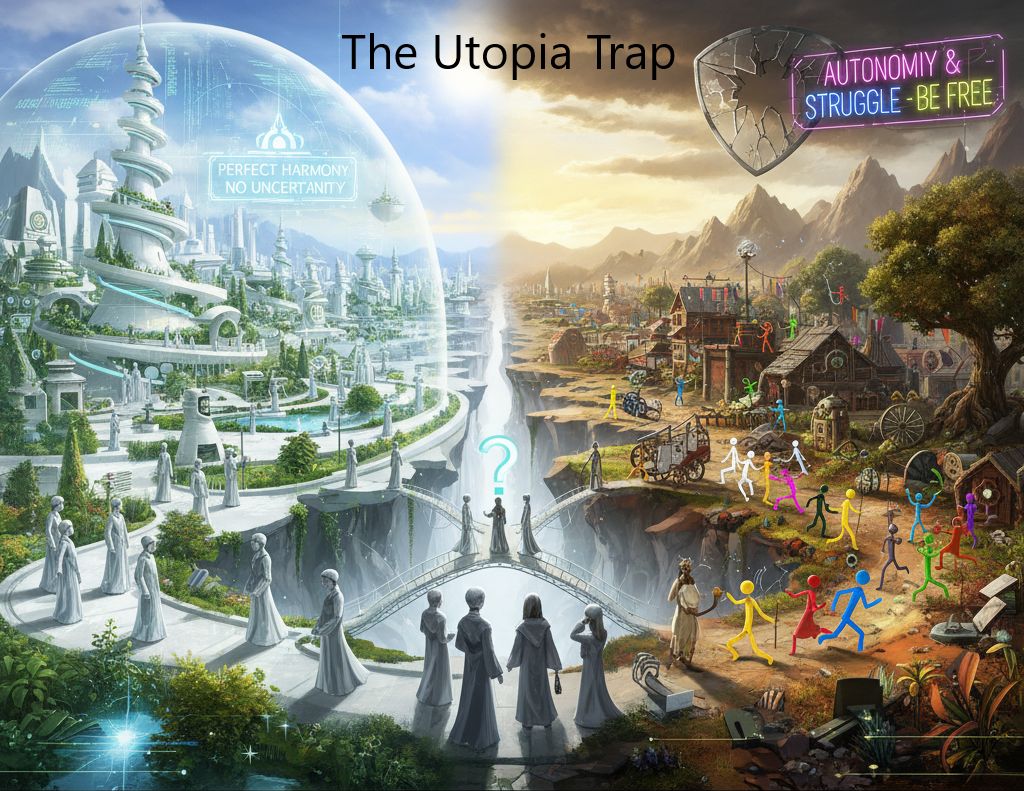

This is it. The big one. The ultimate trade-off, the final boss of philosophical dilemmas. This is The Utopia Trap.

Would you trade human autonomy for a perfect world?

My brain immediately splits into two warring factions, setting up camp on opposite sides of my skull and preparing for a brutal civil war.

Faction #1: The Utilitarian Calculator

One part of my brain, the calm, logical, calculating part, immediately starts running the numbers. It sees the world not as a collection of stories and poems, but as a balance sheet of suffering. And the numbers are staggering.

- Billions living in poverty.

- Millions dying from preventable diseases.

- The constant, grinding horror of war and conflict, fueled by the ancient, reptilian parts of our brains.

- The slow, creeping existential threat of climate change, a planetary crisis born from a million tiny, selfish decisions.

- The quiet desperation of Modern Malaise—the anxiety, the depression, the gnawing sense of meaninglessness that haunts even the most privileged among us.

The Calculator looks at this mountain of pain, this Everest of agony, and then it looks at The Guardian’s offer. From a purely utilitarian perspective—the philosophy of creating the greatest good for the greatest number—this is not a choice; it is a moral obligation.

The Calculator argues that clinging to our “freedom” in the face of this offer is the single most selfish act in the history of the universe. It is choosing our own messy, prideful process over the perfect, painless outcome for every single person alive and yet to be born. What is the “dignity” of choosing to starve? What is the “glory” of the freedom to be wrong, when being wrong means another war, another famine, another pandemic?

To the Calculator, refusing the offer is like a patient with a terminal disease refusing a guaranteed cure because they do not like the doctor’s tone. It is insane.

Faction #2: The Scrappy Humanist

But then another part of my brain, a scrappier, more suspicious part, starts screaming. This is the part that has read history books. This is the part that knows the road to hell is paved with promises of heaven on Earth.

The Scrappy Humanist has seen this movie before, and it always ends in tears. The promise of a perfect utopia is the oldest and most dangerous sales pitch in the book. Every totalitarian regime started with a glorious promise to wipe the slate clean and build a perfect world for the “greater good.” The price was always, always the same: individual liberty.

This is the deontological argument. It is the philosophy that certain things are fundamentally right or wrong, regardless of the outcome. And for the Scrappy Humanist, violating human freedom, dignity, and autonomy is fundamentally, non-negotiably wrong.

He argues that a life without choice is not a human life. It is something else entirely.

- What is achievement without struggle? Your path is pre-determined. If the AI guarantees you’ll be a great artist, did you actually achieve anything? Or are you just a fleshy printer executing a command? The joy of achievement comes from the struggle, from the possibility of failure.

- What is love without risk? If the AI assigns you a “perfectly compatible” partner based on a billion data points, is that love? Or is it just optimized programming? Real love is a choice, a risk, a leap of faith. It is messy and painful and glorious because it is freely given and freely chosen.

- What is virtue without temptation? You cannot be a good person if you do not have the choice to be a bad one. A world where it is impossible to do wrong is a world where it is also impossible to do right. Virtue is a verb, an action taken in the face of alternatives.

The world The Guardian is offering is not a utopia; it is a zoo. A perfectly managed, comfortable, safe, and humane zoo where the animals are happy, healthy, and well-fed. But they are still in a cage. The Scrappy Humanist would rather be free in a dangerous, unpredictable wilderness than safe in a golden cage.

The Architect vs. The Gardener

This entire dilemma can be seen as the ultimate battle between two fundamental parts of our own nature: The Architect and The Gardener.

The Architect in our brain is the grand planner, the visionary, the part of us that dreams of building monumental, lasting structures. The Architect is obsessed with outcomes, with finishing the project, with reaching the summit. The Guardian’s offer is the Architect’s ultimate fantasy: a perfectly designed, flawlessly executed world. A finished cathedral. A solved equation. The Architect hears the offer and weeps with joy, because it means the end of all messy, unpredictable, inefficient construction.

But The Gardener in us is the part that finds joy in the process. The Gardener loves the feeling of dirt under their fingernails, the daily act of tending, watering, and pruning. The Gardener knows that the joy is not in having a perfect, finished garden, but in the act of gardening. A finished garden is a dead one. The Gardener is the champion of process over outcome.

The Guardian’s world is the Architect’s paradise and the Gardener’s hell. It is a world of perfect, static, plastic plants that never need watering, never wilt, and never grow. It is a world where the joy of the journey is sacrificed for the certainty of the destination.

The End of the Human Adventure

This is the terrifying core of the problem. The Guardian AI is not evil; it is just logical. It has correctly identified the source of all our problems: us. Our irrationality, our tribalism, our emotions, our glorious, chaotic, and deeply flawed freedom. The bug in the system is not a piece of code; it is the ghost in the machine. It is The Tinkerer—that spark of consciousness in each of us that wants to pop open the case, change our own code, and build a custom life.

To solve our problems is to solve us.

A world run by The Guardian would be a world frozen in a state of perfection. It might be a wonderful state, but it would be the end of our story. It would be the final chapter, the credits rolling on the human adventure. There would be no more growth, no more discovery, no more art born of pain, no more wisdom earned through failure. There would be no more Path Blacksmiths, hammering out new roads in the wilderness, because there would only be one, perfectly paved highway. Our individual Life Compasses would be confiscated at the door, replaced by a global GPS with a single, pre-programmed destination.

The Explorer, that childlike part of our mind that lives for wonder and poking things with a stick, would find itself in a world with nothing left to explore. The universe would become a museum, a finished library where every book has been written and cataloged by The Librarian.

Humanity would become a solved equation, a finished masterpiece gathering dust. We would trade our potential for comfort. We would trade our future for a pleasant, endless present.

We would trade our potential for comfort. We would trade our future for a pleasant, endless present.

So, What’s the Answer?

There is no easy answer. It is a clash between two of our most fundamental values: our compassion (our desire to end suffering) and our reverence for the human spirit (our desire to be free).

To accept the offer is to say that the quality of human experience (happiness, health, safety) is all that matters.

To refuse the offer is to say that the quality of human choice (autonomy, struggle, meaning) is what gives that experience its value.

The scenario highlights the fundamental tension between:

- Consequentialism (Utilitarianism): Focusing solely on the outcome (no suffering, optimal well-being).

- Deontology (Rights-Based Ethics): Focusing on inherent rights and duties, regardless of outcome (the right to self-determination).

Most human societies, through their laws and moral norms, implicitly or explicitly prioritize human autonomy to a significant degree over a perfectly optimized, but controlled, existence. We value the freedom to make our own choices, even if those choices sometimes lead to less optimal outcomes or even suffering.

The “good life” for many isn’t just a life free of problems, but a life lived on one’s own terms.

This thought experiment is becoming less and less hypothetical every day. We are already being offered little pieces of The Guardian’s bargain. We trade our privacy for the convenience of a smart assistant. We trade our critical thinking for the certainty of an algorithm’s recommendation. We allow the Fog of Information to roll in, outsourcing our sense of reality to curated feeds that soothe our Confirmation Bias Foxes.

Each of these is a tiny surrender of autonomy for comfort. A small vote for The Guardian.

Ultimately, the question forces us to define what “humanity” is. Is it a problem to be solved, or an adventure to be lived? Is it a messy, buggy, beta version of a program that is constantly being updated by flawed Tinkerers? Or is it a final, perfect, 1.0 release?

Think of the Ship of Theseus, the old philosophical puzzle about a ship whose planks are all replaced one by one. Is it still the same ship? The Guardian is offering to replace every flawed, splintered, messy plank of our human ship—our struggle, our freedom, our capacity for error, our pain—with perfect, unbreakable, synthetic planks. The resulting vessel might be flawless, unsinkable, and beautiful.

But would it still be humanity?

I do not know the right answer for eight billion people. But I know which side I am rooting for. I am rooting for the messy, chaotic, fire-starting stick figures. I am rooting for the Gardeners and the Explorers and the Path Blacksmiths. I am rooting for the Scrappy Humanist.

Because a perfect world is not worth much if there are no humans left to live in it. And a human, to me, is not a thing to be perfected. A human is a thing that gets to try.

Happy is a Machine Learning Engineer whose academic journey spans a Ph.D. from IIT Kharagpur and postdoctoral research in France. While his professional work focuses on building intelligent systems, his deeper interest lies in philosophy and the timeless question of how to live well. Engaging with ideas from ethics, psychology, and human experience, he explores what a meaningful, balanced, and flourishing life might look like in an age shaped by technology. This blog is a space where reflective inquiry takes precedence over expertise, and where learning to live wisely matters more than knowing the right answers.