We live in a loud world. A world of roaring engines, flashing screens, and a relentless, humming pressure to do more, be more, and have more. We are cartographers of our own misery, meticulously mapping our progress against the phantom achievements of others. This is the landscape of Modern Malaise—a low-grade, chronic anxiety born not from the threat of a saber-toothed tiger, but from the tyranny of a thousand unanswered emails and the silent, crushing weight of our own expectations.

Our brains, running on ancient survival software, are not built for this. The Primal Panic Button, once reserved for genuine threats, is now triggered by a critical comment on a social media post. The Social Survival Mammoth, that deep, instinctual part of us that fears exile from the tribe, now runs rampant in a global village of eight billion people, whispering that we are falling behind, that we are not enough. We feel its modern manifestation as the Judgmental Parrot on our shoulder, squawking critiques and comparisons until we are paralyzed.

We are told to hustle, to grind, to dream big, to climb the highest mountain. We fix our eyes on a distant summit, believing that happiness is a flag to be planted at the peak. We endure the grueling ascent, ignoring the beauty of the trail beneath our feet, only to find the summit is windy, cold, and offers only a fleeting view before we are compelled to seek another, higher peak. We are told to build a perfect life, to curate a flawless existence, terrified to ship anything—a project, a relationship, a version of ourselves—that is less than 100% complete.

But what if there is another way? What if, instead of adding more to our lives, we could find peace by embracing a different philosophy? What if the answers we seek are not in the roar of the hustle, but in the quiet whispers of ancient wisdom?

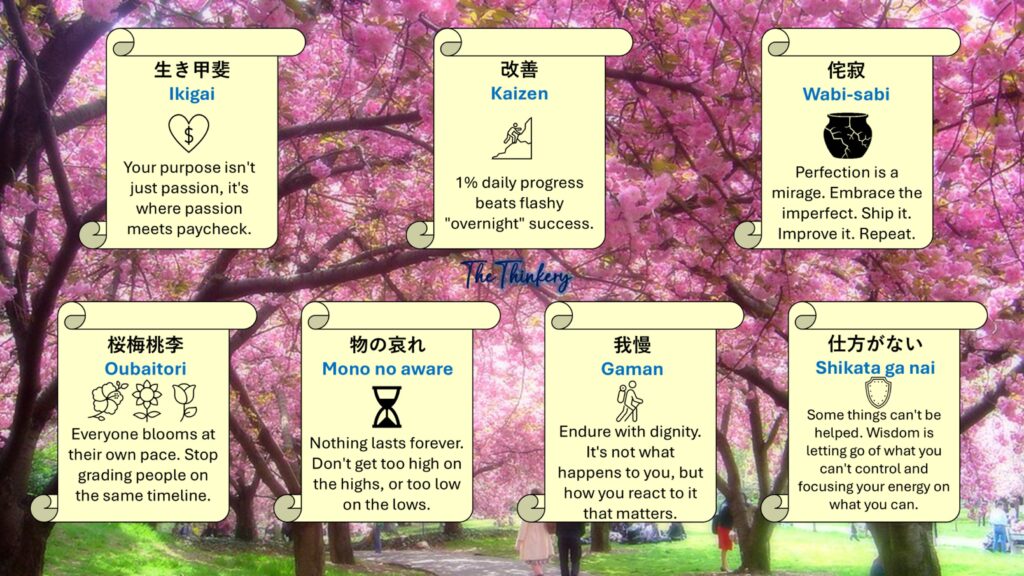

For centuries, Japan has cultivated a series of concepts that offer a profound alternative to the frantic pace of modern life. These are not life hacks or productivity tips. They are deep, resonant ideas that act as a gentle catalyst, inviting us to a quiet moment of reflection. They are a set of tools for the Tinkerer within us—that curious, conscious part of our mind that wants to pop open the case of our own programming and build a custom life.

Let us explore seven of these Japanese whispers. Let them be a balm for the over-stimulated mind, a compass for the lost soul, and a guide to finding grace, purpose, and stillness in a world that never stops shouting.

1. Ikigai (生き甲斐): The Symphony of Purpose and Paycheck

We are often presented with a false dichotomy: you can either follow your passion or you can earn a good living. One path leads to the starving artist, the other to the soul-crushed corporate drone. We are taught to separate our Life Compass—that quiet, inner voice that points toward what makes us feel alive—from the practical demands of the world.

The Japanese concept of Ikigai offers a more integrated vision. Often translated as “a reason for being,” Ikigai is not a single, fiery passion. It is a convergence, a harmonious intersection of four fundamental questions:

- What do you love? (Your passion)

- What are you good at? (Your vocation)

- What does the world need? (Your mission)

- What can you be paid for? (Your profession)

Ikigai is the sweet spot in the center, the place where your personal joy and your public utility become one. It’s the recognition that your purpose isn’t just a self-indulgent quest; it’s a dialogue between your soul and society. It’s where your passion meets a paycheck, not as a compromise, but as a confirmation that your unique gifts have found a home in the world.

Finding your Ikigai is not a weekend workshop affair. It is the life’s work of a Path Blacksmith—the part of you willing to get its hands dirty, to hammer and shape a road that doesn’t exist on anyone else’s map. It requires the curiosity of an Explorer, who treats the world as a giant, interactive question mark, and the patience of a Gardener, who understands that things bloom in their own time.

Imagine a woman who loves the intricate art of baking (what she loves). Over the years, she becomes exceptionally skilled at creating complex pastries (what she is good at). She notices that her town lacks a place where people can gather and connect over quality, handmade food, a place that fosters community (what the world needs). So, she opens a small bakery. The community flocks to her shop, not just for the bread, but for the warmth and connection she provides. She earns a comfortable living doing what she loves, for people who value it (what she can be paid for). She has not just found a job; she has found her Ikigai.

This is a powerful antidote to the modern pressure to be a Workhorse, mindlessly checking off tasks for a goal you don’t believe in. The Workhorse derives a fleeting sense of accomplishment from an empty inbox, a temporary dopamine hit that fades as quickly as it arrives. But the person living their Ikigai is fueled by a deeper, more sustainable energy. Their work is not a transaction; it is an expression of their very being.

To find your Ikigai, you must silence the Backseat Choir—the internalized voices of parents, teachers, and society telling you what you should be. You must learn to listen to the whisper of your Life Compass, even when the world is shouting. It is a journey of self-discovery, of experimentation, and of courage. It is the ultimate act of building a Custom OS for your life—one where your work is not what you do, but who you are.

2. Kaizen (改善): The Gentle Art of 1% Progress

Our culture is obsessed with the myth of overnight success. We celebrate the lottery winner, the viral sensation, the disruptive startup that seemingly came out of nowhere. We are a society hooked on the myth of the single dramatic breakthrough—one heroic leap instead of a thousand quiet steps. We glorify the headline moment and ignore the invisible compounding of small, repeated acts. This mindset, however, is a recipe for disappointment and burnout. It teaches us to devalue the small, consistent efforts that are the true bedrock of all meaningful growth.

Kaizen offers a quieter, more sustainable path. Translating to “continuous improvement,” Kaizen is a philosophy that champions small, incremental changes made consistently over time. It is the belief that 1% progress every day is infinitely more powerful than a flashy, short-lived burst of effort.

This is the philosophy of the Gardener. The Gardener does not expect a barren patch of land to become a lush garden overnight. They do not stand in the field and shout at the seeds to grow faster. Instead, they show up every day. They pull a few weeds. They add a little water. They turn the soil. They trust in the power of small, consistent actions. Day by day, the changes are almost unnoticeable. But over weeks, months, and years, the transformation is profound.

Each small action, each tiny win, triggers the Winner Effect. This is the self-reinforcing cycle where each success, no matter how small, boosts our confidence and makes the next win more likely. Answering one email doesn’t feel like much, but it’s a win. Going for a five-minute walk is a win. Reading one page of a book is a win. These small victories are the kindling that builds the fire of momentum.

Consider someone who wants to get in shape. He can sign up for a marathon, buy expensive gear, and commit to a brutal two-hour workout every day. This often leads to injury, exhaustion, and quitting within a few weeks. The Kaizen approach is to start by walking for five minutes a day. The next week, maybe it’s ten. The week after, a little more. They add one more vegetable to their dinner. They swap one soda for a glass of water. These changes are so small they feel insignificant. But compounded over a year, they result in a complete transformation of health and lifestyle—one that is sustainable because it was built brick by brick, not thrown together in a frantic rush.

Kaizen is not about a lack of ambition. It is about a smarter, more humane way of achieving it. It is about falling in love with the process, not just the outcome. It is about recognizing that the master is not the one who takes the biggest leap, but the one who takes the most steps.

3. Wabi-sabi (侘寂): The Courage to Ship It Imperfect

We live in a world that worships the flawless. We airbrush our photos, curate our online personas, and polish our work until it gleams with an unnatural perfection. We have internalized the voice of the Quality Pope, the high priest of perfectionism in our minds who tells us that anything less than 100% is a failure. This pursuit of perfection, however, is often a gilded cage. It paralyzes us, kills our momentum, and keeps our best work locked away in a drawer, forever “almost ready.”

Wabi-sabi is the antidote to this paralysis. It is a worldview centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. It is the art of finding beauty in things that are incomplete, impermanent, and unconventional. Wabi-sabi is the cracked ceramic bowl, mended with gold. It is the recognition that the flaws, the history, and the imperfections are what give an object—or a person—its character and its soul.

For the creator, the entrepreneur, the artist—for anyone trying to bring something new into the world—Wabi-sabi is a liberating philosophy. It is the courage to ship it imperfect. It is the understanding that momentum is more valuable than perfection. The Tinkerer within us knows this instinctively. The Tinkerer loves to experiment, to debug, to iterate. A clunky version 1.0 that is out in the world, getting feedback and evolving, is infinitely better than a mythical version 3.0 that never sees the light of day.

Perfectionism is often just fear in a fancy coat. It is the Judgmental Parrot on our shoulder, squawking that if it’s not perfect, everyone will laugh. It is the Social Survival Mammoth telling us that if we show our flaws, we will be cast out of the tribe. Wabi-sabi invites us to tell these ancient voices that they are running on outdated software.

In the world of software development, there is a concept called the “Minimum Viable Product” (MVP). The goal is not to launch a perfect, feature-complete product. The goal is to launch the simplest possible version that solves a core problem, get it into the hands of real users, and then iterate based on their feedback. This is Wabi-sabi in action. It is a dance between creation and feedback, a process of evolution rather than a singular act of immaculate conception.

Think of your own life. How many projects have you abandoned because they weren’t “good enough”? How many ideas have withered on the vine of your own self-criticism? Wabi-sabi gives you permission to be a beginner. It gives you permission to be messy. It gives you permission to be human.

Embracing Wabi-sabi does not mean embracing sloppiness or a lack of standards. It means understanding the difference between excellence and perfection. Excellence is a worthy pursuit. It is about doing your best with the resources you have. Perfection is a mirage. It is a finish line that moves every time you get close.

So, write the messy first draft. Launch the simple website. Have the awkward conversation. Ship the imperfect product. Embrace the beauty of the incomplete. You can always mend it with gold later.

4. Oubaitori (桜梅桃李): The Freedom to Bloom in Your Own Season

From a young age, we are placed on a conveyor belt of comparison. We are graded, ranked, and measured against our peers. We are taught to believe in a single, linear timeline for success: good grades, then a good college, then a good job, then marriage, then a house, then children. This creates a Scoreboard Philosophy where we are constantly looking at someone else’s score to determine our own worth. This relentless comparison is a primary fuel source for the Status Anxiety that defines so much of modern life.

The Japanese concept of Oubaitori offers a powerful liberation from this trap. The word is a compound of the kanji for four different trees that bloom in the spring: the cherry (桜), the plum (梅), the peach (桃), and the apricot (李). The phrase is a reminder that each of these trees blooms in its own time, in its own way, and each is beautiful in its own right. You would not criticize the plum for not being a cherry, nor the apricot for blooming later than the peach.

Oubaitori is the radical idea that we should apply this same logic to ourselves. It is the wisdom to stop grading people—including ourselves—on the same timeline. It is the understanding that everyone has their own unique path, their own unique talents, and their own unique season of blooming.

This concept is a direct challenge to the Mirage Factory of social media, which manufactures and broadcasts idealized versions of reality at an unprecedented scale. We scroll through a highlight reel of other people’s lives—their promotions, their exotic vacations, their perfect families—and we mistake their curated image for their reality. Our Reality Window becomes smudged with the fingerprints of comparison, and we begin to believe that our own messy, complicated, behind-the-scenes life is somehow deficient.

Oubaitori invites us to clean that window. It reminds us that we are all different “human genres.” Some of us are Artisans, finding joy in the slow process of creation. Some are Explorers, driven by an insatiable curiosity. Some are Guardians, whose purpose is to nurture and protect their pack. To compare an Artisan’s quiet satisfaction with an Explorer’s thrilling discovery is to compare the beauty of a plum blossom to that of a cherry. It is a meaningless comparison.

Someone might find their Ikigai and build a successful company in their twenties. Another might spend decades raising a family, only to discover a passion for painting in their sixties. One person’s “bloom” is a bestselling novel; another’s is a quiet life of service to their community. Oubaitori teaches us that all of these paths are valid and beautiful.

Embracing Oubaitori means focusing on your own garden. It means celebrating your own progress, no matter how small it may seem. It means running your own race, on your own terms. It is the ultimate act of self-compassion, a declaration of independence from the tyranny of comparison. It is the quiet confidence of knowing that you are a cherry tree, and you will bloom in your own magnificent time.

5. Mono no aware (物の哀れ): The Bittersweet Beauty of Impermanence

Of all the anxieties that haunt the human mind, the fear of endings is perhaps the most pervasive. We dread the end of a vacation, the end of a relationship, the end of a project, and, ultimately, the end of our own lives. We cling to the present moment, desperately trying to hold on to what is good, and we suffer when it inevitably slips through our fingers.

The Japanese concept of Mono no aware offers a different way of relating to the transient nature of life. It translates roughly to “the pathos of things,” “an empathy toward things,” or “a sensitivity to ephemera.” It is a gentle, bittersweet sadness for the reality that all things are impermanent. But crucially, it is not a despairing sadness. It is a deep, appreciative awareness that it is the very impermanence of things that gives them their beauty and their value.

The classic example is the Japanese love for cherry blossoms (sakura). The blossoms are breathtakingly beautiful, but they last for only a week or two before they fall. The experience of hanami (flower viewing) is not just about admiring the beauty of the flowers; it is about being deeply present with their impermanence. If the blossoms lasted all year, would we still gather in parks to celebrate them with such reverence?

Mono no aware emphasizes the impermanence of events and experiences. Recognizing that situations and emotions are temporary can reduce anxiety during difficult times. The awareness that “this, too, shall pass” can be a profound comfort. That stressful project at work that feels all-consuming? It is temporary. That difficult season in your life that feels like it will never end? It is a cherry blossom, and it will fall.

But Mono no aware is not just for the difficult times. It is also for the joyful times. It is a reminder to be fully present with the good moments, precisely because they will not last. It is the quiet joy of watching your children play, knowing that this phase of life is fleeting. It is the deep appreciation for a beautiful sunset, knowing that the colors will soon fade to black. It is the ability to savor a perfect cup of tea, knowing that the warmth and the flavor are temporary.

This awareness transforms our relationship with time. Instead of constantly chasing the next thing, driven by the Dopamine Donkey that rewards seeking over arriving, we can learn to find richness in the present moment. Mono no aware is the enemy of the “I’ll be happy when…” mindset. It teaches us that happiness is not a destination; it is a practice of appreciating the now, in all its fleeting beauty.

“Mono no aware” is a mature, reflective state of mind. It is the quiet wisdom that understands that life is a series of hellos and goodbyes. By embracing the bittersweet reality of impermanence, we can learn to hold our joys more tenderly and our sorrows more lightly. We can learn to live with a greater sense of gratitude, presence, and peace.

6. Gaman (我慢): The Quiet Dignity of Endurance

Life is difficult. There will be times of hardship, disappointment, and pain that we cannot avoid. In the face of such challenges, we often preach a philosophy of “grinding harder,” of becoming a Steamroller that flattens obstacles through sheer force of will. Or, conversely, it encourages a culture of complaint, where we allow the Chief of Personal Grievances in our brain to build endless cases against the world for our suffering.

Gaman offers a third path. It is a Zen Buddhist term that is often translated as “endurance,” “patience,” or “perseverance.” But it is more than just gritting your teeth and bearing it. Gaman is about enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity. It is about maintaining self-control and discipline in the face of adversity. It is about resilience, but a quiet, internal resilience, not a loud, aggressive one.

Gaman is not about suppressing emotions. It is about choosing a mature and graceful response to them. It is the understanding that while we may not be able to control the external events of our lives, we can control our reaction to them. This is the core teaching of Stoicism, and it finds a powerful echo in the concept of Gaman.

Imagine two people who have lost their jobs. The first person is consumed by anger and resentment. They spend their days complaining, blaming their former boss, and sinking into a spiral of negativity. Their Chief of Personal Grievances is working overtime, and their energy is drained by the constant internal courtroom drama.

The second person, practicing Gaman, also feels the pain, fear, and disappointment of the job loss. They do not deny these feelings. But they choose not to be defined by them. They accept the reality of the situation and focus their energy on what they can control: updating their resume, reaching out to their network, learning a new skill. They carry their hardship with a quiet dignity, not as a sign of weakness, but as a testament to their inner strength. They are not “grinding harder”; they are enduring with grace.

Gaman is about protecting your emotional energy. It is the wisdom to know that some battles are not worth fighting, and that some complaints only serve to poison our own well. It is the strength to show up, day after day, and do what needs to be done, even when it is difficult, without losing your composure or your sense of self.

In a world that encourages us to broadcast our every grievance, Gaman is a quiet rebellion. It is the understanding that true strength is not measured by how loudly you can shout, but by how calmly you can endure. It is the inner peace that comes from knowing that you have the capacity to weather any storm with your dignity intact.

7. Shikata ga nai (仕方がない): The Liberating Power of Acceptance

There is a close cousin to Gaman that is equally powerful and perhaps even more liberating. It is the phrase Shikata ga nai, which translates to “it cannot be helped.”

At first glance, this might sound like a philosophy of passive resignation, a justification for giving up. But that is a profound misunderstanding of its power. Shikata ga nai is not about giving up on the things you can change; it is about having the wisdom to accept the things you cannot. It is a tool for radical acceptance, a surgical instrument for separating what is in your control from what is not.

Our minds are constantly trying to solve the unsolvable. We replay past mistakes, wishing we could change them. We worry about future events that are completely outside of our influence. We rage against the fundamental nature of reality—that people get sick, that accidents happen, that things end. We expend vast amounts of emotional energy on these unwinnable battles, draining ourselves in the process.

Shikata ga nai is the act of stamping “CASE CLOSED” on these unsolvable files. It is the recognition that your energy is a finite and precious resource, and it is foolish to waste it on things that are beyond your control.

Think of being stuck in a massive traffic jam. You can honk your horn, you can curse the other drivers, you can let your blood pressure skyrocket. Your Primal Panic Button is flashing, and your Chief of Personal Grievances is screaming about the injustice of it all. But none of this will make the traffic move any faster. The situation “cannot be helped.”

The Shikata ga nai response is to take a deep breath, accept the reality of the situation, and shift your focus to what you can control. You can listen to a podcast. You can call a friend. You can simply sit in silence and observe your own frustration without judgment. This is not passivity; it is a strategic reallocation of your energy. It is protecting your peace.

This concept is the ultimate tool for the Tinkerer. A good engineer knows which parts of the system they can modify and which parts are fixed. They don’t waste time trying to rewrite the laws of physics. They focus their creative energy on the variables they can actually influence. Shikata ga nai is the art of identifying the fixed parts of your life’s equation so you can pour all your energy into solving for the variables.

When faced with a difficult situation, ask yourself: “Is there anything I can do to change this?” If the answer is yes, then act. But if the answer is no, then the wisest and most powerful thing you can do is to whisper to yourself, “Shikata ga nai,” and let it go. This is not weakness. This is the highest form of wisdom. It is the key to unlocking a vast reservoir of energy and peace that you have been wasting on unwinnable wars.

The Gardener’s Path

These seven concepts are not a checklist to be completed. They are a garden to be cultivated. They are whispers that, if you listen closely, can guide you back to a more human, more sustainable way of being.

- Ikigai is the seed of purpose, the blueprint for a life where work is an expression of love.

- Kaizen is the daily watering, the small, consistent act of showing up for your own growth.

- Wabi-sabi is the acceptance of the slightly imperfect fruit, finding beauty in the real, not the ideal.

- Oubaitori is the celebration of the diverse flowers in the garden, the release from the poison of comparison.

- Mono no aware is the gentle appreciation of the fleeting bloom, the practice of being present with both its beauty and its sadness.

- Gaman is the strong root system that holds firm in the storm, the quiet dignity of endurance.

- Shikata ga nai is the wisdom of the gardener who does not rage against the rain, but accepts it and knows that it, too, is part of the process.

Together, they offer a path away from the frantic, noisy world and toward the quiet, fulfilling world of the Gardening Architect—one who holds a vision for the future but finds joy in the daily act of laying each stone.

The world will continue to shout. The Mirage Factory will continue to broadcast its illusions. The Judgmental Parrot will continue to squawk. But with these whispers in your heart, you can choose a different way. You can choose to walk the unpaved path, to cultivate your own garden, and to build a life not of frantic striving, but of quiet, profound, and deeply personal meaning.

Happy is a Machine Learning Engineer whose academic journey spans a Ph.D. from IIT Kharagpur and postdoctoral research in France. While his professional work focuses on building intelligent systems, his deeper interest lies in philosophy and the timeless question of how to live well. Engaging with ideas from ethics, psychology, and human experience, he explores what a meaningful, balanced, and flourishing life might look like in an age shaped by technology. This blog is a space where reflective inquiry takes precedence over expertise, and where learning to live wisely matters more than knowing the right answers.