Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine Asks a Question

It is a quiet afternoon. You are sitting in your chair, and a question, unbidden, floats into your mind. Without a second thought, you speak the question into the air. A small, disembodied voice from a plastic cylinder on your counter responds instantly, its answer crisp, accurate, and utterly devoid of wonder.

You have just outsourced a portion of your memory and curiosity to a machine. You have performed a small miracle that would have been indistinguishable from magic to any human who lived just a century ago. And then, you move on. You check your email.

We live our lives immersed in a sea of beautiful, terrifying, world-altering inventions, yet we have become so accustomed to them that they are mostly invisible. But what if we stopped for a moment and looked closer? What if we asked a deeper question: If we are the creators of our tools, are our tools not also the creators of us?

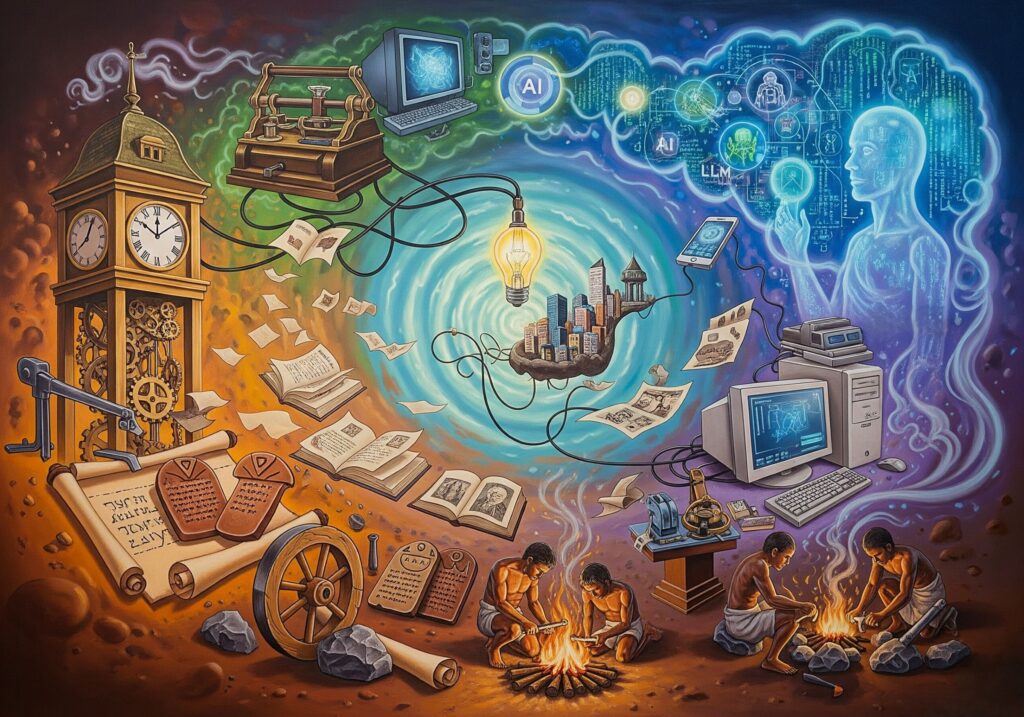

This is a story about that relationship. It is a journey into how a series of beautiful inventions—from the first controlled flame to the glowing screens we hold in our hands—have not just changed what we do, but have fundamentally rewired who we are. They have sculpted our brains, reshaped our societies, and redefined the very essence of our humanity. We are all born with our Factory Settings—the biological and cultural programming of our time. But our inventions are the software updates that have been pushed to our species over millennia, each one altering the source code of our lives.

We are, at our core, the Tinkerer—the ghost in the machine that can’t resist popping open the case to see how things work. We invent to solve problems, to extend our reach, to satisfy our curiosity. But the fascinating twist in our story is that every time we invent a new tool, the tool invents a new kind of human. This is the story of that co-creation.

Part 1: The First Sparks – Fire, Tools, and the Birth of the Modern Mind

Before we were us, we were just another clever primate. We were creatures of instinct, our days dictated by the rising and setting of the sun, our lives governed by the raw, unfiltered input of our senses. Our internal world was likely a storm of primal urges. Survival was the only game in town.

Then, we did something no other species had ever done. We tamed fire.

Fire: The First External Stomach and the Birth of the Living Room

On the surface, fire was a tool for warmth, for protection from predators, for light in the darkness. But its most profound impact was quieter and far more transformative.

By cooking our food, we outsourced a massive portion of the digestive process. Tough fibers and proteins that once took our bodies immense energy to break down were now pre-processed by the flames. This simple act freed up a huge surplus of metabolic energy. And that energy went straight to our heads. Our brains, the most energy-hungry organs in our bodies, began to grow at an explosive rate. The Tinkerer in our skulls was suddenly given a massive power upgrade.

But fire did more than just build a better brain. It built a new kind of social space. The campfire became the first human living room. Before fire, darkness was a time of fear and isolation. After fire, the night became a time for community. Around the flickering flames, we were no longer just a collection of individuals. We were a tribe.

This was the first taste of power, the first hit of the Winner Effect on a species-wide scale. We won a victory against the dark, and our inner caveman grunted in approval, releasing a flood of dopamine that would drive us to conquer again and again.

This was the birthplace of culture. It was here that the first stories were told, the first myths woven. It was here that we began to share our thoughts, our fears, our plans for the next day’s hunt. Language, which may have started as simple warnings and commands, could now blossom into narrative, into history, into shared identity. The campfire was where we first learned to be us. It was the original social network, a place where the software of culture was first written and installed directly into our newly expanding minds. It was here that the Backseat Choir of societal norms began to tune its voice, where the tales of heroes and villains laid the first tracks of our moral software.

The Stone Tool: The First Extension of Thought

At the same time we were taming fire, we were chipping away at stones. A sharpened rock seems primitive to us now, but it was a revolution. For the first time, we were extending our will into the world through a physical object. Apes might use a stick to get termites, but we were designing tools. We were holding a rock and seeing, in our mind’s eye, the axe or the spearhead hidden within it.

This was the birth of abstract, multi-step thinking. To make a stone tool, you had to:

- Imagine a future need (e.g., “I will need to butcher an animal later”).

- Form a mental template of the tool required.

- Find the right raw materials.

- Execute a precise, planned sequence of actions to shape the stone.

This process was a workout for the brain’s frontal lobes, the seat of planning and foresight. With the stone tool, we outsourced the brute force of our teeth and hands to an object, projecting our will into the world with newfound power. It was the physical manifestation of the thought: “If I do this now, I can achieve that later.” The tool was not just an object; it was a thought, made tangible. It was the first time we took an idea from inside our heads and gave it a durable, physical form in the world.

With fire and stone tools, we were no longer just reacting to our environment; we were beginning to shape it. We were taking the first tentative steps from being creatures of instinct to becoming authors of our own destiny. The world was no longer just a place we lived in; it was a place we could act upon. This was the single most important cognitive leap in human history, and it was all powered by our first, beautiful inventions.

Part 2: The Great Reorganization – Agriculture, Writing, and the Invention of Order

For hundreds of thousands of years, we were wanderers. We were hunters and gatherers, living in small, egalitarian bands, our lives dictated by the seasons and the migration of animals. Our social software was simple, designed for the intimate dynamics of a small tribe. The Social Survival Mammoth in our brains was calibrated to a world where we knew everyone and social harmony was paramount.

Then, about 12,000 years ago, another beautiful invention took root: agriculture. And with it, everything changed.

Agriculture: The Invention of Tomorrow (and Anxiety)

Agriculture was, at its heart, the invention of the future. As hunter-gatherers, our lives were lived almost entirely in the present. We found food, we ate it. The concept of a surplus was foreign. But farming required a radical new way of thinking. It demanded that we invest our labor now for a reward that might not come for many months. We had to have faith in a future that did not yet exist.

This was a profound rewiring of the human mind. With agriculture, we outsourced the daily, uncertain task of finding food to the slow, predictable work of the land. It forced us to develop a long-term perspective. We had to plan, to save seeds, to track the seasons, to build calendars. We had to invent the concept of “work” as a sustained, goal-oriented effort, distinct from the immediate task of finding the next meal. The Dopamine Donkey in our brains, once satisfied with the instant reward of a ripe fruit, was now being trained to chase the much more distant carrot of a future harvest.

But this invention came with a dark side. With the future came anxiety. As hunter-gatherers, our stresses were acute and immediate—a predator, a sudden storm. These were the threats our Primal Panic Button was designed for. But agriculture introduced a new kind of stress: chronic, low-grade, and perpetual.

What if the rains don’t come? What if a blight destroys the crops? What if we don’t have enough to last the winter?

Read more about: The Epic Journey of Human Worry & Suffering: Evolution of Anxiety

This was the birth of Modern Malaise in its earliest form. We had traded the immediate dangers of the wild for the gnawing, existential dread of the harvest. We had created a world of abundance, but also a world of worry.

Furthermore, agriculture tethered us to the land. We settled down. Villages grew into towns, and towns into cities. For the first time, we were living among strangers. The Social Survival Mammoth, which had evolved for life in a small tribe where everyone knew their place, was now adrift in a sea of unfamiliar faces. This was the dawn of a new and powerful anxiety: Status Anxiety. In a city, you were no longer just you; you were your land, your surplus, your position in a newly forming hierarchy.

The Wheel: The Invention of Effortless Motion

For millennia, our world was as large as our own two feet could make it. To move anything heavy was a monumental task, a battle against friction and gravity that required the brute force of many. The world beyond our immediate vicinity was distant and difficult to reach.

Then, a simple yet profound invention appeared: the wheel. With the wheel, we outsourced the tyranny of friction to a rolling object, conquering distance and making the world smaller.

Initially used for pottery, the wheel’s true power was unleashed when it was turned on its side and put on an axle. Suddenly, a single person could move what once required a team. Carts and chariots appeared. Goods could be transported over long distances, connecting distant communities and creating the first trade routes. The world began to shrink.

This had a profound effect on our minds. The wheel introduced a new concept: mechanical advantage. It was a physical demonstration that a clever system could multiply human effort exponentially. It was a testament to the power of a good idea. The Tinkerer in our minds, who had been chipping stones, now had a new toy, one that rolled and spun and opened up a world of possibilities.

This new mobility also meant that societies could grow larger and more complex. Cities could be supplied with food and resources from a wider radius. Armies could be moved with terrifying speed, and empires could be built and maintained across vast territories. The wheel was the engine of the first empires. It was the tool that allowed a centralized power to project its force outward.

The wheel was the first great network technology. It connected points on a map, creating a grid of commerce and conflict. It broke down the isolation of communities and began the long, messy process of weaving humanity into a single, interconnected story. It taught us that the limits of our bodies were not the limits of our world. We were no longer just living on the land; we were redesigning it to suit our needs. This was a new level of mastery over our environment, and it paved the way for the empires and interconnected civilizations to come.

Writing: The First External Brain

As our cities grew, they became too complex to manage with spoken words and human memory alone. How do you track who owned which plot of land? How do you record the grain stored in the city’s granaries? How do you pass down laws to a population of thousands?

The solution was another beautiful invention: writing.

With writing, we outsourced our collective memory to clay tablets and papyrus, creating a permanent, shareable mind outside of our own skulls. Writing began as a simple accounting tool—a way to keep track of grain and livestock. But like fire, its true impact was far more profound. Writing was the world’s first external brain.

Before writing, a society’s knowledge was limited to what its people could collectively remember. History was oral, passed down through generations, and as fluid and fallible as human memory itself. When an elder died, a library burned to the ground.

Writing changed that. It allowed us to take our thoughts, our stories, our laws, and our discoveries and store them outside of our own skulls. For the first time, knowledge could be accumulated, passed down with perfect fidelity, and built upon by future generations. It was the birth of history, of science, of philosophy. It allowed for a level of complexity and abstraction in thought that was simply not possible before.

Think of the Librarian in your mind, the part of you that organizes and categorizes information. Before writing, this librarian had to keep the entire library in their head. It was a monumental and ultimately impossible task. Writing gave the Librarian shelves. It gave them a card catalog. It allowed for the creation of a vast, shared, external library of human knowledge.

This had a powerful effect on our individual minds as well. Writing encourages a different kind of thinking—more linear, more logical, more structured. It allows you to lay out an argument, to review it, to refine it. It is no coincidence that the birth of writing was followed by an explosion in law, mathematics, and philosophy in places like Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece. We were not just writing down our thoughts; the act of writing was shaping the very way we thought.

The invention of writing was the single most significant leap in the history of information technology. Early forms like cuneiform and hieroglyphs were revolutionary, but they were complex and required years of training. They were the domain of a specialized class of scribes. The true democratization of writing came with the phonetic alphabet—a system so elegant and simple that a child could learn it. It was a system where a small number of symbols could be combined to represent any spoken sound, and therefore, any idea.

With agriculture and writing, we had reorganized our world. We had built cities, created hierarchies, and invented a way to conquer time and memory. We had become organized, civilized, and deeply anxious creatures.

Part 3: The Mechanical Age – The Clock, the Press, and the Taming of the Soul

For most of human history, time was a natural, cyclical phenomenon. It was the rhythm of the sun, the moon, the seasons. It was fluid, organic, and local. “Noon” was simply when the sun was highest in the sky, and that moment was slightly different for everyone.

Then, in the late Middle Ages, a new machine began to appear in the town squares of Europe: the mechanical clock. And with it, time was forever changed.

The Clock: The Invention of “Now”

The mechanical clock was a revolutionary invention. By inventing the clock, we outsourced our internal, biological sense of time to an external, mechanical authority. It took time, which had always been a natural process, and turned it into a mathematical, abstract, and universal grid. The day was no longer just sunrise, midday, and sunset. It was now divided into 24 precise, equal, and unyielding hours.

This was a profound shift in human consciousness. We began to live by the clock, not by the sun. Work was no longer task-oriented (“I will shear the sheep until I am done”); it became time-oriented (“I will work from 9 to 5”). Time was no longer something we inhabited; it was a resource to be spent, saved, wasted, or managed. “Time is money” is not an ancient proverb; it is the slogan of the world the clock created.

The clock created a new kind of pressure. It synchronized society. Factory whistles blew, and thousands of people started and stopped working at the exact same moment. Trains ran on schedules, and being “on time” became a moral virtue. The clock was the operating system of the Industrial Revolution, a tool for coordinating the complex machinery of modern life.

This new conception of time seeped into our souls. We began to see our own lives as a finite resource, a line segment of hours and minutes stretching from birth to death. The Someday Slug, that creature in our minds that loves procrastination, was now locked in a battle with the ticking clock. We developed a new kind of anxiety: the fear of running out of time. We became obsessed with productivity, efficiency, and the relentless march of progress. We became masters of managing our time, but we risked becoming strangers to the timeless moments of joy, contemplation, and connection that give life its meaning. The ticking of the clock became the soundtrack of modern life, a constant reminder of the one thing we could never make more of.

The Printing Press: The First Information Explosion

For centuries after the invention of writing, books were rare and precious objects. Each one had to be copied by hand, a laborious process that made them accessible only to a tiny elite of monks and nobles. The vast library of human knowledge existed, but it was locked away.

Then, around 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press with movable type. And the world caught fire.

With the printing press, we outsourced the act of cultural replication from the fallible hand of the scribe to the perfect fidelity of the machine.

The printing press was the internet of its day. It made it possible to reproduce information quickly, cheaply, and on a massive scale. The price of books plummeted. Literacy, once the domain of the elite, began to spread to the masses. For the first time in history, ideas could go viral.

This had world-shattering consequences. The Protestant Reformation was fueled by printed pamphlets that challenged the authority of the Catholic Church. The Scientific Revolution was made possible by the rapid dissemination of new discoveries and theories. The Enlightenment was a conversation that took place in printed books and journals across Europe.

The printing press democratized knowledge. It took the power to shape the public narrative away from the centralized control of the church and state and put it into the hands of individuals. It created the very concept of “public opinion.”

But this first information explosion also created a new set of problems. With more information came more misinformation. How could you know what to trust? The Exhausted Librarian in our brains, once responsible for a small, curated collection, was now faced with a flood of new books, many of them contradictory or heretical. This was the beginning of the modern challenge of information overload.

The printing press also changed our sense of self. As people began to read in private, they developed a richer inner life. The novel, a new literary form that emerged in the wake of the printing press, allowed people to enter the minds of fictional characters, fostering a new sense of empathy and psychological depth. We began to see ourselves as individuals with unique, complex inner worlds. The modern concept of the “self” was born, in part, from the quiet, solitary act of reading a printed book.

With the clock and the printing press, we had tamed time and democratized knowledge. We had become punctual, literate, and individualistic. We had also become more anxious, more overloaded with information, and more aware of our own mortality. The stage was set for the next great leap.

Part 4: The Electric Age – The Telegraph, the Lightbulb, and the Death of Distance

For all of human history, the speed of information was tied to the speed of a horse or a ship. To send a message across a continent or an ocean took weeks or months. The world was a vast, disconnected place. An event happening in Europe would not be known in America until long after it was over.

Then, in the 19th century, we harnessed the power of electricity. And the world shrank overnight.

The Telegraph and Telephone: The Annihilation of Space

The telegraph was a bizarre and magical invention. With the telegraph, we outsourced the transport of our words from physical messengers to invisible electrical pulses. By sending pulses of electricity down a wire, we could transmit complex messages almost instantaneously across vast distances. It was the first time that communication was decoupled from transportation.

The impact was staggering. Financial markets, which once operated on local information, were now connected in real time, creating a single global economy. Newspapers could report on events from across the country on the same day they happened, creating a shared national consciousness. Wars were fought and directed via telegraph wires.

The telephone took this a step further. It transmitted not just dots and dashes, but the human voice itself. The disembodied voice on the other end of the line was a ghost, a miracle, a presence that defied all known laws of reality. It allowed for an intimacy and immediacy that the telegraph lacked.

These inventions rewired our brains and our societies. They created a sense of a perpetual, interconnected “now.” We were living in a world where an event anywhere could be an event everywhere. This was exhilarating, but also overwhelming. The Primal Panic Button, designed for local threats, was now being triggered by news from thousands of miles away. We developed a new kind of global anxiety, a sense of being responsible for, and vulnerable to, events far beyond our personal control.

The Lightbulb: The Conquest of Night

Just as fire had pushed back the darkness of the primordial night, the electric lightbulb conquered it completely. With the lightbulb, we outsourced the regulation of our daily cycle from the sun to a switch on the wall. With the flick of a switch, we could banish the night and create a perpetual day.

This had a profound impact on our lives and our biology. The natural rhythm of sleep and wakefulness, which had governed life for eons, was now disrupted. We could work, play, and live 24 hours a day. The “night shift” was born. Cities blazed with light, fundamentally altering the nocturnal environment for ourselves and every other creature.

This conquest of night fueled an explosion of productivity and culture. But it also came at a cost. We are only now beginning to understand the deep impact of artificial light on our circadian rhythms, our mental health, and our connection to the natural world. For most of human history, the night sky was a source of wonder, a canvas for myths and philosophy. The stars were our calendar and our compass. Today, for the majority of humans living in cities, the Milky Way is a forgotten memory, washed out by the glow of our own beautiful invention.

With the electric age, we had annihilated distance and conquered the night. We had created a single, interconnected global village, blazing with perpetual light. We had become gods of space and time. But we had also untethered ourselves from the natural rhythms that had shaped us for millions of years, and the consequences of that unmooring are still unfolding.

Part 5: The Digital Age – The Computer, the Internet, and the Rewiring of Everything

If the last 10,000 years were about reorganizing our external world, the last 50 have been about reorganizing our internal one. The digital revolution, powered by the computer and the internet, is an invention so vast and so intimate that we are still in the very early stages of understanding what it is doing to us.

The Computer: The Universal Machine

The computer is a different kind of invention from all those that came before it. The clock tells time. The car provides transport. The computer, however, is a universal machine. It is a machine that can become any other machine. It is a tool for manipulating not matter, but information. If writing allowed us to store our thoughts, the computer allowed us to store our logic. It was the externalization of a part of the thinking process itself.

Early computers were behemoths, filling entire rooms, dedicated to complex calculations for science and war. They were the domain of a new priesthood of programmers and technicians. But the real revolution, as with the alphabet, was in miniaturization and accessibility. The personal computer brought this power into the home and the office.

With the personal computer, we outsourced countless cognitive tasks—from calculation to categorization—to a silicon brain on our desk. It was a calculator, a typewriter, a filing cabinet, a drawing board, and a communication device, all in one. It achieves this by running on a simple, powerful principle: software. This separation of the machine (hardware) from its function (software) was a profound conceptual breakthrough.

It changed the way we work, the way we create, and the way we think. It encouraged a kind of modular, logical, systems-based thinking. One could now achieve in an hour what once took a week. But it also raised the bar. The new expectation was not just to do the work, but to use these new tools to do it faster and better. The focus of many jobs shifted from performing the task to managing the software that performed the task.

The Internet: The Global Brain and the Mirage Factory

With the internet, we outsourced the storage of human knowledge from libraries to a decentralized, instantly accessible global network. The internet connected all of these universal machines together, creating something akin to a global brain. For the first time in history, almost all of the world’s accumulated knowledge was available, almost instantly, to anyone with a connection. This was the ultimate fulfillment of the promise of the printing press.

The social internet, which came next, was the fulfillment of the promise of the campfire. It allowed us to connect, to share, to form tribes not based on geography, but on shared interests and beliefs. It has been a source of immense community, comfort, and collective action.

But this global brain has a dark and chaotic side. The internet is not just a library; it is a battlefield. It is a space where the Confirmation Bias Fox runs wild, and where the AI Chameleon can generate plausible falsehoods at an infinite scale. We are living in a state of perpetual Fog of Information, where the line between truth and fiction is dangerously blurred.

The internet has also become a powerful Mirage Factory. It presents us with a curated, filtered, and impossibly perfect version of reality. We are constantly comparing our messy, complicated, behind-the-scenes lives with the highlight reels of others. The Social Survival Mammoth, already anxious in the big city, is now driven into a state of perpetual panic by the silent, scrolling judgment of billions. We are lonelier, more anxious, and more depressed than ever, in part because we are living in a world where everyone else’s life looks perfect.

The Smartphone and LLMs: The Final Frontier is Inside Us

The internet was a place you “went to.” You sat down at a desktop computer, you “logged on,” and you entered another world. The invention of the smartphone collapsed that distance. It took the global brain of the internet and put it in our pockets. The distinction between “online” and “offline” began to dissolve. There was no longer a place you went to; the network was simply with you, always.

With the smartphone, we outsourced our moment-to-moment awareness to a pocket-sized oracle, a constant connection to everything and everyone, everywhere. It is a Swiss Army Knife for the Soul, a tool that promises to meet our every need for information, connection, and validation. It is a permanent, umbilical connection to the entire world of information and social pressure. It is a dopamine-dispensing machine of unprecedented power, and it has colonized our attention and our minds in ways we are only beginning to grasp. Our ability for deep focus, for quiet contemplation, for boredom—all essential for creativity and self-reflection—is under constant assault.

This merged self, this human-smartphone hybrid, is a powerful entity. We have access to more information and more connection than any humans in history. But it is also a vulnerable one. We have outsourced parts of our memory, our attention, and our social judgment to a device whose operating system is often designed not for our well-being, but for the profit of its creators in Silicon Valley.

And now, we stand at the precipice of the next great invention: Large Language Models and Artificial Intelligence. With LLMs, we are beginning to outsource the very act of creation—our writing, our art, our ideas—to a non-human intelligence. These are not just tools for finding information; they are tools for creating it. They are not just extensions of our memory; they are becoming extensions of our creativity and our consciousness.

We are outsourcing our writing, our coding, our art, and even our conversations to these machines. What will that do to us? When we no longer need to struggle through the process of writing to clarify our thoughts, will our thoughts become less clear? When we can generate a beautiful image with a simple prompt, what happens to the skill and the soul of the artist? When we can have a perfectly agreeable conversation with an AI, what happens to our ability to navigate the messy, difficult, and beautiful reality of human relationships?

This is the Utopia Trap in its most seductive form. The promise is a world without friction, without effort, without struggle. But what if that friction, that effort, that struggle, is where the meaning is? What if, in our quest to build a perfect world, we engineer ourselves out of the very things that make us human?

Conclusion: The Tinkerer’s Choice

Our journey from the first campfire to the glowing screen in our hand is a testament to the restless, creative, and world-altering power of the human mind. We are the Tinkerer, and we cannot help but invent. Each invention has been a beautiful, double-edged sword. It has solved a problem, and in doing so, created a new one. It has extended our power, and in doing so, revealed a new vulnerability. It has made us more connected, and more alone. More powerful, and more anxious.

- We offloaded our stomachs to fire and got the time for thought.

- We outsourced the brute force of our teeth and hands to a stone tool.

- We tamed the wild with agriculture and found our food by planting and harvesting, not just hunting and gathering.

- We conquered distance with the wheel and built empires.

- We externalized our memory with the alphabet and created history.

- We democratized knowledge with the printing press and sparked revolutions.

- We caged our lives with the clock and built the industrial world.

- We bridged distant minds with the telegraph and telephone, turning continents into instant conversation.

- We invented the light bulb, turning night into extra hours for work, creativity, and connection.

- We externalized our logic with the computer and created a digital reality.

- We connected our minds with the internet and built a global brain.

- We merged with our tools with the smartphone and became cyborgs.

- And now, with LLMs, we are conversing with a mirror of our own collective mind.

The story of our inventions is the story of a creature slowly and often accidentally building its own cage. We have built a world of clocks and schedules, of global networks and information overload, of social pressures and digital distractions. This is the modern human’s environment, and it is profoundly unnatural.

But the story is not over. The final and most beautiful invention is not yet complete. It is the invention of the self.

We are the first generation in history to be consciously aware of our own programming. We can see the Factory Settings we were born with. We can feel the pull of the Social Survival Mammoth. We have the ability to look at the vast and complex operating system that our inventions have built for us, and we can choose to rewrite the code.

This is the ultimate task of the Tinkerer. It is not to build a better machine, but to build a better self. It is to consciously choose our values, to cultivate our attention, to build a Custom OS that allows us to thrive in the world we have created. It is to learn to be a Gardening Architect, balancing our grand ambitions with the simple, present joy of being alive. It is to use our beautiful inventions not as masters, but as tools, in the service of a life that is intentional, meaningful, and truly our own.

The ghost in the machine is no longer just asking trivial questions. It is asking the most important question of all: In a world of our own making, who do we choose to be?

References:

Happy is a Machine Learning Engineer whose academic journey spans a Ph.D. from IIT Kharagpur and postdoctoral research in France. While his professional work focuses on building intelligent systems, his deeper interest lies in philosophy and the timeless question of how to live well. Engaging with ideas from ethics, psychology, and human experience, he explores what a meaningful, balanced, and flourishing life might look like in an age shaped by technology. This blog is a space where reflective inquiry takes precedence over expertise, and where learning to live wisely matters more than knowing the right answers.